July is coming, which for most people in the United States means barbeques, fireworks, and hoping desperately that you have air conditioning. But for the medical profession, July is a time for new beginnings, when interns shed their now-filthy short, white coats of medical students for the slightly longer pressed white ones of physicians. Medical school graduations vary significantly throughout the US — having come from New Orleans, mine involved Bloody Marys, indoor pyrotechnics in the Superdome, and the Dalai Lama dancing with a second line umbrella to Dr. John and Alan Toussaint. But even the most staid graduation ceremony involves the invocation of some sort of oath, commonly called the Hippocratic Oath.

The Dalai Lama at the Tulane Convocation. This is literally what it looked like.

In popular imagination, it sounds something like this:

“Remember your oath” is popular trope in medical shows during heated ethical moments (TV Tropes link here) and the appeal of the oath, for lay and medical audiences alike, is obvious — it places modern physicians as part of a long and unbroken tradition tracing back to the origins of medicine. It’s an attractive picture — Hippocrates, toga-clad, Maimonides and the Arab physicians, Vesalius and Galen in their Dutch blacks, the great Enlightenment doctors, all the way to modern luminaries like Osler and Salk, solemnly reciting the same oath. But it’s really nothing more than an attractive fiction. The modern tradition of reciting the oath has far less to do with respect for history and much more to do with an understandable reaction to the very modern horrors that physicians perpetrated in the 20th century.

Jonas Salk, inventor of the polio vaccine

But first let’s start at the beginning, in the fifth century before the common era in the area that is now Greece and western Turkey. The history of the Oath starts with the man whose name it bears — Hippocrates of Kos, which is an island near the Turkish resort town of Bodrum. Regarded — rightly or wrongly, which is the topic of another podcast — as the father of medicine, during his life he was a highly respected physician who left an impressive corpus of dozens of works. Hippocratic medicine was based on the four humors and was not terribly effective, but he introduced important innovations into the practice of medicine, including naturalism, humanism, and empiricism. Some of his observations are still useful today — most notably clubbing in respiratory disease. But probably his most persistent contribution was the oath that was attributed to him, which sets the precept that a physician’s duty is to his patient, whether a king, commoner, or a slave.

Kos. Not a shabby place to be from.

The original Oath starts with its famous invocation of the healer-gods of the ancient world: “I swear by Apollo the physician and Asclepius the surgeon” and touches on a number of topics that are recognizable to the modern physician — imploring physicians to teach the next generation, to give good dietetic advice to their patients, and to keep patient-doctor confidentiality — and some that are a little more incongruent with the modern world, including a ban against having sex with your patient’s slaves, a ban on abortion, and of course, an entreaty against ever doing surgery, to never “cut for stone”. And the Hipprocratic school meant business: the final line implores the gods to protect them, but to also to brutally punish them if they dare violate their oath.

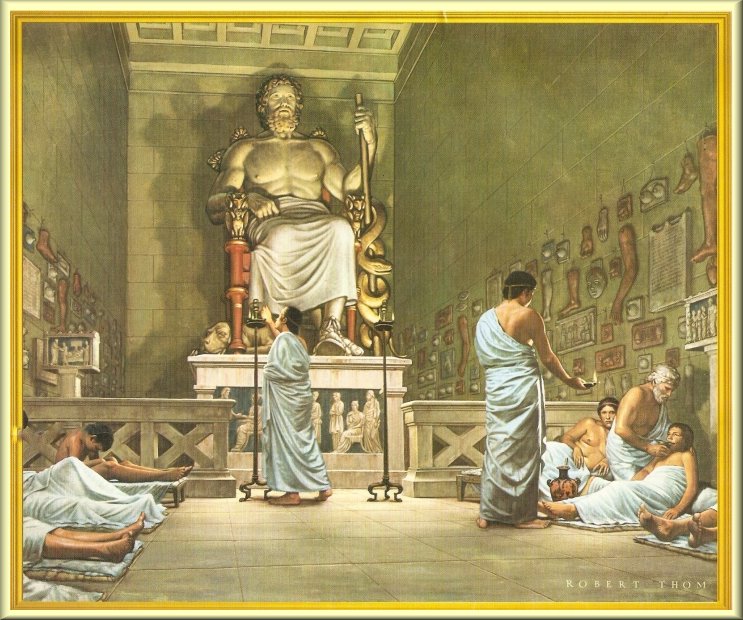

Ascelpius, a god who means business. From an awesome series of paintings by Robert Thom.

After presumably being used by the ancients, the oath disappears for almost 2000 years. The Renaissance saw an influx of Greek texts via the Arabs, and ancient Greek ideas of naturalism and observation began to dominate Western medical thought again. In fact, there isn’t another mention of the Oath until 1508, when it was used during a graduation ceremony at the University of Wittenberg in Germany. Throughout the Enlightenment, the Hippocratic Oath, along with its monotheistic cousin, the Oath of Maimonides, were used sporadically by medical schools for their graduating physicians. There’s some thought that the pagan overtones of the Hippocratic Oath may have prevented it from becoming more widespread, though it certainly did spread gradually — by 1928, about 1 in 5 medical schools offered some sort of Oath on graduation, usually that of Hippocrates or Maimonides. Just 70 years later, a study found that 100% of medical schools in the United States and Canada used some sort of oath.

So what happened?

It takes only passing knowledge of the 20th century to figure that one out. Decades of scientific racism and medical eugenics — spearheaded in the United States, I should remind any American who feels a level of ethical superiority — came to their logical conclusion in Nazi Germany. Nazi doctors — and let’s not forget that 40% of physicians belonged to the Nazi party in Germany — performed horrific experiments on prisoners, amputating limbs, inducing hypothermia, forcing them to drink seawater to simulate battle injuries, purposely infecting children with tuberculosis, typhus, and syphilis, and performing horrific vivisections on awake Jewish prisoners to find out what made the Jewish race so uniquely inferior. Many drugs were tested on Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, and other undesirables, including the forerunners of modern sulfa antibiotics.

A Nazi prisoner immersed in freezing water in Dachau, submitted as evidence at the Nuremburg Doctors’ Trial.

Nazi physicians likewise traced themselves back to Hippocrates. Mrugowsky, the SS physician in charge of the battle injury trials, reinterpreted Hippocrates’ words, breaking down the division between healing and research, since medical research benefited the “Volk”, which of course exclusively included the “Aryan” people. Even Himmler, the head of the SS, wrote in a guide for SS physicians called “Eternal Doctors” about, “the great Greek doctor Hippocrates,” of the “unity of character and accomplishment” of his life, which “proclaims a morality, the strengths of which are still undiminished today and shall continue to determine medical action and thought in the future.”

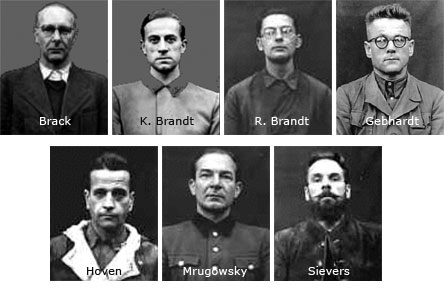

Much of the horror of the Nazi medical experiments — which I want to stress again, are only different from what happened in the U.S. by magnitude and not their intent; I would encourage anyone who doubts that to read about Tuskegee or forced sterilization — was hidden from the world in the fog of war. All that changed during the Nuremberg Doctor’s Trial held after the war. With almost 140 days of proceedings, testimony of 85 witnesses and victims, and almost 1,500 documents laying out grisly details of Nazi medical experimentation , the world bare witness to what physicians were capable of. 16 of the 23 doctors at the trial were found guilty, and seven, including Mrugowsky, were hanged.

The seven physicians who were hanged.

Interest in a new oath began almost immediately. In the second meeting of the World Medical Association, formed at the same time as the United Nations and initially representing 27 nations, the world’s pre-eminent physicians immediately set out updating the Hippocratic Oath. Their product is called the Declaration of Geneva, which is what you heard in that Gray’s Anatomy segment. Notable additions, clearly spurred by Nazi and Japanese experiments during the war, include:

I will maintain the utmost respect for human life; and

I will not use my medical knowledge to violate human rights and civil liberties, even under threat

An updated version of the Hippocratic Oath, written by awesomely-named Dr. Louis Lasagna of Tufts University, was made in the 60s that, along with the Declaration of Geneva, rapidly proliferated through the United States. It contains some choice barbs for the modern physician, including, “avoiding those twin traps of overtreatment and therapeutic nihilism”, not being ashamed to say “I know not”, and a solemn remembrance that “I do not treat a fever chart, a cancerous growth, but a sick human being.” It also removes language against abortion, euthanasia, surgery, and sex with slaves, and removes any reference to religion, either ancient or modern.

Dr. Louis Lasagna, courtesy of the NIH.

The Hippocratic Oath or the modified version above is used in roughly half of medical schools. The other half use the Declaration of Geneva or a version authored by faculty or students. When I graduated from Tulane — two long years ago — my school had just abandoned a modified version of the Hippocratic Oath for one written by faculty and students at the University. Draped in silly green robes that would be more appropriate for a Harry Potter convention than the start of a career for 150 physicians, I remember being apathetic about our oath, which to me seemed like a nice set of rules but an antiquated tradition. But I’ll just go ahead and admit it — like most medical students, I was wrong. The Oath has its origins in the ancient past, but its importance is fundamentally modern. It’s a reminder of the horrors our profession is capable of, horrors that were perpetrated in only the recent past. And it’s a warning against such behavior in the future.

Two years ago, an independent group of medical professionals found that military physicians at Guantanamo Bay had violated both their oaths and medical ethics by taking part in the torture of prisoners there. And while the American Psychiatric Association and American Medical Association determined that their code of medical ethics prevented their members from taking part in “interrogations,” the American Psychological Society publically announced that ‘it is consistent with the APA Ethics Code for psychologists to serve in consultative roles to interrogation and information-gathering processes for national security-related purposes,” and it is alleged that psychologists, with approval from the highest levels of the APA itself, helped design the government’s torture program.

Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Our Oaths are also germane in current debates about physicians’ roles in executions. Regardless of your view of the death penalty, there are a substantial number of doctors — myself included — who feel that it is incongruent to swear that “Primum non nocere” — above all, do no harm — and then proceed with performing a medical procedure, often placing a central line, and using drugs to execute an inmate. In one of the few good things my home state has done recently, in 2007 the North Carolina Medical Board ruled that any doctor who participated in an execution would violate their code of ethics and be subject to license revocation. This was later overturned by the state Supreme Court, but the debate lives on.

A death chamber.

2,500 years have passed since the time of Hippocrates, and after getting over the whole printing press, electricity, flight, television, internet shock, I’m sure he’d be surprised that his oath is still referenced. Because doctors today do “cut for stone.” They do provide safe and legal abortion. And in my state, and a smattering of other places across the world, they have begun to provide “death with dignity”, or physician-assisted suicide. We also don’t have slaves. But I also think he’d recognize the fundamental similarity of spirit in our Oaths, a recognizance of the great evil that our profession is capable of, and the importance of committing ourselves to the good of our patients above all. And while he might hope for vengeful gods of healing to keep us faithful to that Oath, he might recognize the wrath of Apollo and Asclepius in our professional societies and medical boards. FYI, that was definitely a joke.

Sources:

The Hippocratic Oath Today, includes the full text of the original Hippocratic Oath and the updated version

The Declaration of Geneva, from the World Medical Association

Emery A, Hippocrates and the Oath, Journal of Medical Biography. November 2013.

Nazi Medical Experiments, The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Hulkower, R. The History of the Hippocratic Oath: Outdated, Inauthentic, and Yet Still Relevant

Lifton, R. The Nazi Doctors: Medical Killing and the Psychology of Genocide. 1986.