Everyone knows the story of Phineas Gage, the young man who had a tamping iron shot through his brain in a freak accident and miraculously survived, only to have extreme personality changes. But the true story is far more complex — and more interesting. In Episode 16 of Bedside Rounds, I revisit the primary sources on Gage’s injury, delve into modern research into what actually happened, and take a field trip to visit the man himself.

I’m trying something different in this post — more media, less words. Hopefully this will supplement your enjoyment of the podcast!

You like my bumper music? Not familiar with the story of Phineas Gage? Let Banjo Dan and the Mid-nite Plowboys recount it for you:

Fun fact: Banjo Dan and the Mid-nite Plowboys come from the Green Mountains in Vermont, not far from Phineas’ home in Cavendish. Our story starts in these mountains, near the town of Cavendish, VT:

Taken from Wikipedia: “North-facing view of “cut” through rock along the former Rutland & Burlington Railroad, 3/4 mile south of Cavendish, Vermont.”

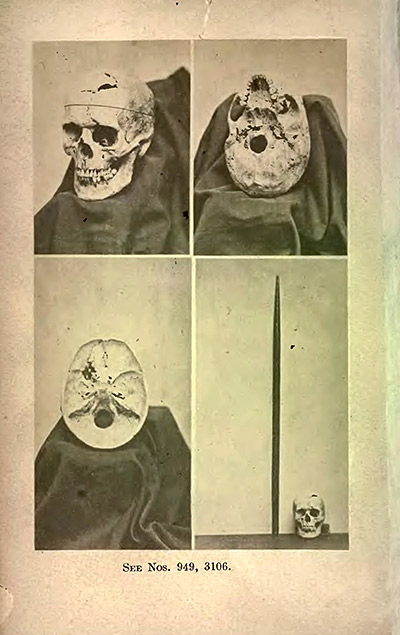

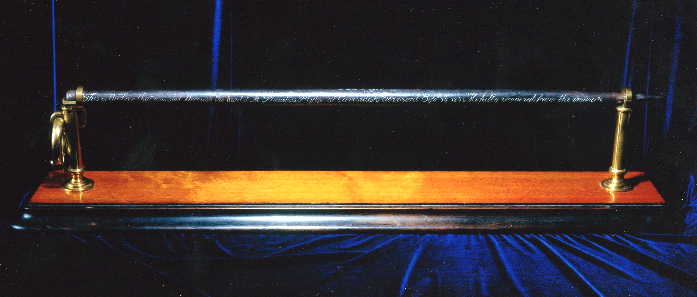

While preparing blasting powder, Phineas accidentally set off a spark which launched the rod pictured below into his skull:

The tamping iron, with its inscription, in the Warren Anatomical Museum in the Harvard Medical School library.

Phineas was immediately taken to local Cavendish physician Dr John M. Harlow’s home for treatment. He kept meticulous note, reproduced in the 1848 publication in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal piece called “Passage of an Iron Rod Through the Head”:

Years later, the Drs. Ratiu, et al recreated the injury using Phineas’ actual skull and advanced imaging techniques:

Digital recreation of Phineas’ injury, from the NEJM piece The Tale of Phineas Gage, digitally remastered.

The researchers also created a video, which you can view here.

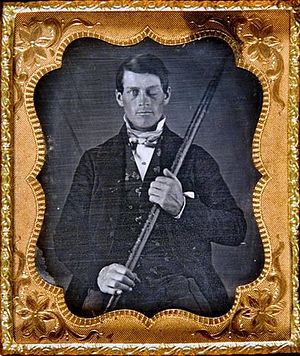

After recovering from his injury, Phineas traveled around New England, lecturing about his injury. The photo below is thought to be of Gage, circa 1850, from this period:

After his injury, Dr. Harlow noted that Phineas underwent extreme personality changes:

The equilibrium or balance, so to speak, between his intellectual faculties and animal propensities, seems to have been destroyed. He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (which was not previously his custom), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operation, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible. … In this regard his mind was radically changed, so decidedly that his friends and acquaintances said he was ’no longer Gage’.

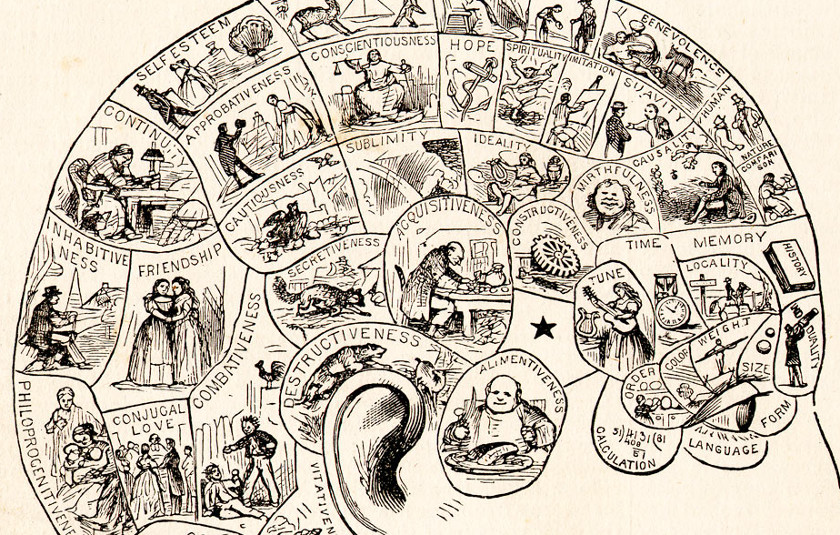

The immediate implication of Phineas’ injury to the burgeoning field of neurophysiology was that certain parts of the brain must be related to executive function. David Ferrier performed famous experiments destroying the prefrontal cortex in monkeys, finding that they would become impulsive and lack self-control. This lay in direct contradiction to the dominant theory of the time: phrenology. Phrenologists thought the brain worked more like this:

Modern neuroscience and psychology has tempered the traditional story of Phineas Gage. Psychologist Malcolm McMillan argues that his personality changes were overblown, and may have just lasted a short time, if at all. In fact, he wrote a book about it. Drs. Ratiu and company, who made the nifty image about, have shown that the destruction of the pre-frontal cortex was far less extensive that Drs. Ferrier and Harlow had presumed.

After Phineas died, his family had his body exhumed, and his skull and the tamping iron were given to Dr. Harlow, then deposited in the Warren Anatomical Museum.

If you’re in Boston, you should give it a visit! Here’s the Atlas Obscura link. It’s free! And quite interesting, though small.

Music Credits:

- Phineas Gage, by Banjo Dan and the Mid-nite Plowboys

- Bass Vibes, Comic Plodding, Folk Round, Iron Horse, Kawaii Kitsune by Kevin McLeod, icompetech.com

Sources:

- Harlow, J. M. (1848). Passage of an iron rod through the head. Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, 39, 389-393.

- Harlow, J.M. (1868). Recovery from the passage of an iron bar through the head Read before the Massachusetts Medical Society 3 June 1868.

- O’Driscoll, Kieran et al. “No Longer Gage”: an iron bar through the head. BMJ. 1998 Dec 19; 317(7174): 1673–1674.

- Ferrier, David. The Goulstonian Lecture on the Localisation of Cerebral Disease. Br Med J. 1878 Mar 30; 1(900): 443–447.

- Ratiu, et al. The Tale of Phineas Gage, Digitally Remastered. NEJM

N Engl J Med 2004; 351.